MLK: Rare Items That Tell The Story of His Life and Times

Rev. Martin Luther King blazed a civil rights trail and left a trail of items to remember him. The Smithsonian NMAAHC offers a few of these for view.

1 / 12

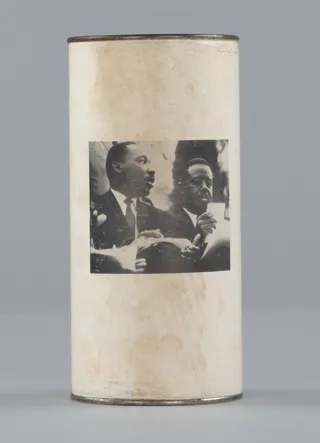

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) was the grassroots organization that piloted the Civil Rights Movement. But in its initial days it raised funds simply by what little people could donate. Donation cans like these were common in churches and other fundraisers.

Photo By Courtesy: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

2 / 12

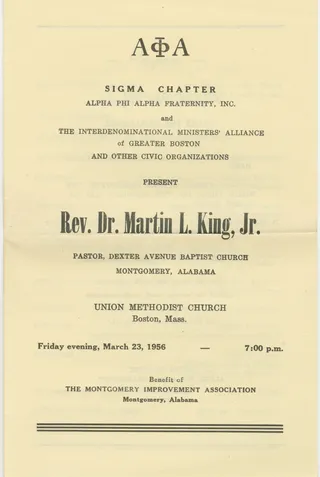

King joined Alpha Phi Alpha in its Boston Metro chapter in 1952. This program is from an appearance he made at the city’s Union Methodist Church in 1956 to benefit the Montgomery Improvement Association, which at the time was in the midst of a boycott of the bus system in Montgomery, Ala.

Photo By Courtesy: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

3 / 12

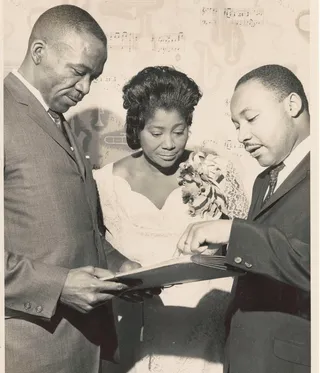

An unidentified man stand with King and singer Mahalia Jackson, who was seen as the soundtrack of the Civil Rights Movement. Jackson was known to appear with King many times as he traveled and sang at the March on Washington in 1963 and at his funeral in 1968.

Photo By Courtesy: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

4 / 12

The March on Washington was not just a rally. It was intended to speak truth to power and it forced an audience with the most powerful in the nation. Here, King is pictured with Civil Rights activist and labor leader A. Philip Randolph, UAW leader Walter Reuther, House Speaker John William McCormack, and House Majority Leader Carl Albert, at the time of the March.

Photo By Courtesy: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

5 / 12

Even President John F. Kennedy and his brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy were moved to work with the Civil Rights movement as they saw its momentum growing. Here they, along with King are pictured with some names that are now historic including Whitney Young, John Lewis, Roy Wilkins and Floyd McKissack among others.

Photo By Courtesy: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

ADVERTISEMENT

6 / 12

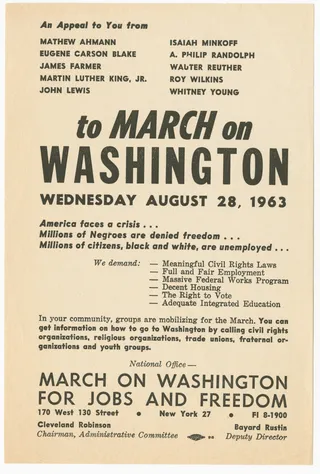

The March was not something that happened in a vacuum. It not only took careful planning and massive buy-in, but a grassroots campaign to get the more than 250,000 people to come. In an age half a century before social media was even a reality, people had to seek information on getting to Washington, which was provided by organizers Bayard Rustin and Cleveland Robinson.

Photo By Courtesy: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

7 / 12

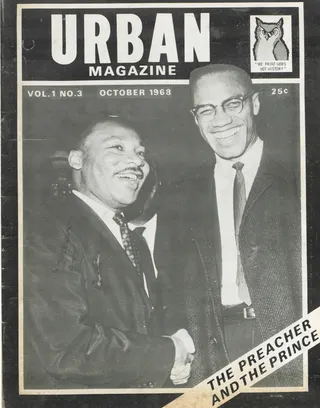

Malcolm X was known to be publicly critical of King and the SCLC. But after his March 1964 split with the Nation of Islam, He sought to bring some unity between his new Organization of Afro American Unity and other civil rights leaders. He and King met briefly in Washington D.C., later that month and exchanged greetings. It was their only meeting. Malcolm spent much of the year putting together the OAAU and traveling overseas. He was assassinated the next February. This cover of Urban magazine shows one of the few images from their meeting.

Photo By Courtesy: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

8 / 12

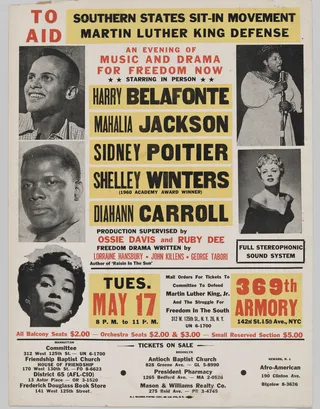

Entertainers, many of whom were victims of Jim Crow and had been forced to enter venues through back doors, were ardent supporters of King and they raised funds to help his legal defense and that of sit-in protesters in the American south who were constantly subject to arrest. Harry Belafonte, Sidney Poitier, Diahann Carroll and Ruby Dee and Ossie Davis were among the many who participated.

Photo By Courtesy: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

9 / 12

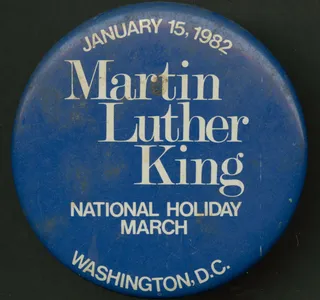

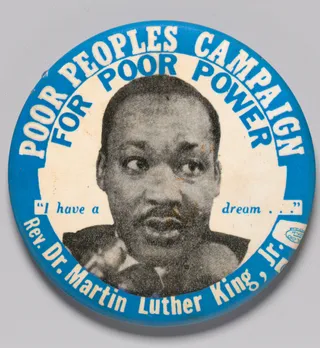

By the latter 1960s, King had begun to focus on economic justice for the poor and marginalized in America and launched his Poor People’s Campaign. Organized labor was a major supporter of his efforts and indeed, he found himself speaking for the rights of workers in America. In 1968, he traveled to Memphis to come to the aid of striking garbage workers when he fell to an assassin’s bullet on April 4. This button is an item passed out to people who supported the campaign.

Photo By Courtesy: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

10 / 12

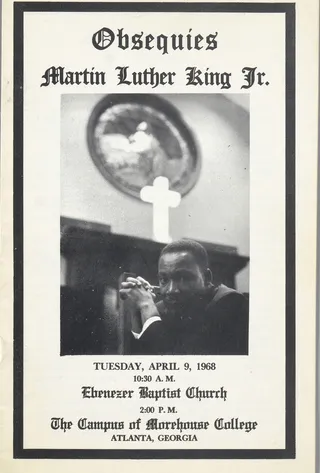

The day of King’s funeral, on April 9, 1968 was one of the most somber events in U.S. history. A horse drawn carriage followed by thousands drew his casket through the streets of Atlanta for services that morning at Ebenezer Baptist Church, where he had preached, and later a public service on the campus of Morehouse College, his alma mater.

Photo By Courtesy: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

ADVERTISEMENT

11 / 12

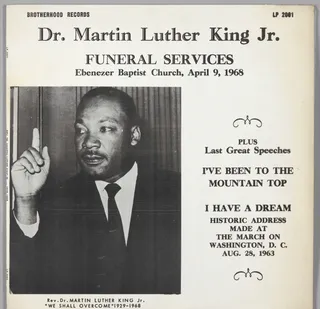

King’s funeral service was as much a national news event as it was in itself a Civil Rights protest. Brotherhood Records released a recording of the service, which featured a eulogy by Rev. Ralph Abernathy and his final speech, “I’ve Been To The Mountaintop,” which he delivered at Mason Temple in Memphis the night before he was killed.

Photo By Courtesy: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture